Part 1: The History of Engineering Natural Habitats

Throughout human history our interactions with animals have been mostly ones of confrontation, either as hunter and prey or master and beast of burden. While menageries have existed since around 3500 BCE as rare examples of wild animals being held in captivity primarily for the pleasure of royalty, it wasn’t until the early 19th century that the function of a zoo changed from a symbol of wealth and royal power to a place for the public to experience the exotic and for scientific study to be conducted.

With the establishment of The London Zoo by the Zoological Society f London in 1828, the standard for all zoos to come afterwards was set, with early enclosures subsisting of dirt and concrete floors with metal bars walling the animals in. While this was better than some earlier animal exhibitions in London, such as the Exeter Exchange, which displayed it’s animals in small mounted enclosures barely big enough for them to turn around in so as to fit them all into a small space.

The concrete enclosure formula was mostly just for the convenience of the human visitors and was likely hell on the animals. In fact current Neuroscience shows us that the environment has a substantial impact not just on behavior but also on the structure of the brain. Living in an environment with no stimulation can cause serious mentally deterioration in animals and researchers like Elizabeth Gould and Diane Lee have been exploring not only how this effects them but also how it could apply to humans in impoverished areas, prisoners in solitary confinement, and also animals in zoos. Research like this is now informing habitat design.

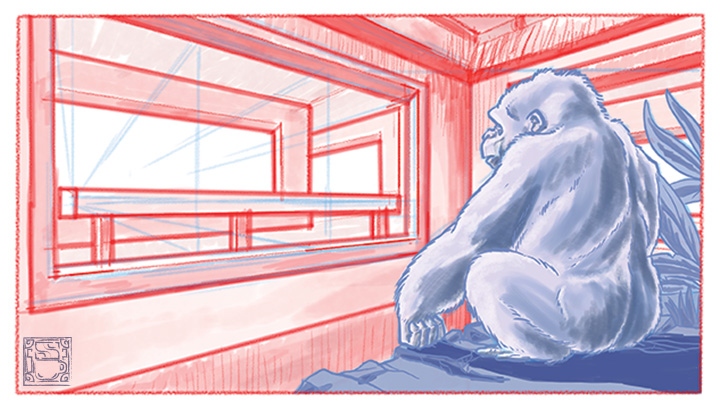

It wasn’t until around the early 1970s when David Hancocks was hired as an architect at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle and found himself in the unique position of not having a boss, as the zoo director had left shortly after him being retired. Hancocks and his team decided to take this opportunity to rethink the whole philosophy in animal enclosure design and decided to start with the gorilla habitat. As with all zoos up until that point, the gorillas lived in what was mostly a concrete box with very little for them to interact with, as a result a lot of them had issues with aggression and would do things like smearing their feces on the walls out of boredom. To rethink this, the team decided to engineer a natural environment for the great apes to live in; the problem being that very little was actually known about gorillas in their natural environment at the time.

Hancock recruited the help of Dian Fossey, who was at the time the preeminent authority on gorillas. With Fossey’s input they went to work tearing up the concrete and replacing it with dirt, hills, rock cliff faces, and trees; adding in lots of natural structures for the animals to climb and interact with. The result was an almost immediate change in the animal behavior. This was of course a gamble, as no one really knew whether or not gorillas raised in concrete structures for their whole lives would even know what to do with a natural environment or whether or not they might freak out from the changes made, but in the end the experiment paid off and other zoos took note. Today most zoological parks incorporate natural settings into almost all of their exhibits, and a new industry of civil engineering has erupted from the sparks made by Hancocks and his team.